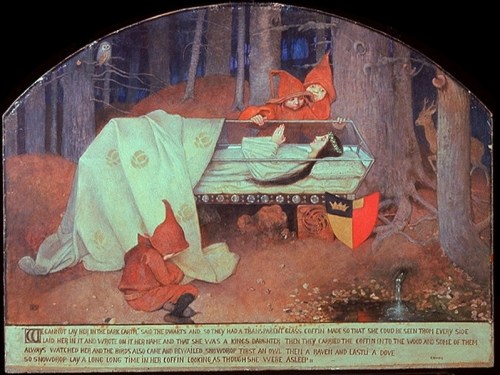

At some point during the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey, the heroine either dies or she’s in disguise. Actually, it’s much the same thing: the heroine essentially loses herself. Snow White dies from the apple and is laid in her glass coffin. Sleeping Beauty sleeps for a hundred years. Cinderella and Donkeyskin are disfigured by ashes and the donkey’s hide: no one knows who they truly are. The Goose Girl is disguised as a goose girl, of course. In “Six Swans” the heroine must stay silent for seven years. Rapunzel is in her tower, just as Sleeping Beauty is in her forest. Vasilisa is in Baba Yaga’s hut, which is a place of the dead. The heroine is immured, lost to the world in some way, and lost to herself. The exception is “Beauty and the Beast”-type tales, which includes “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon.” In those tales, it’s the male love interest who dies or sleeps, who is lost. The heroine’s task is to find him, to recognize him — which as we will see is the next step. But in most of the tales I’m familiar with, it’s the heroine herself who dies or is in disguise for a while.

One of my hypotheses is that the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey pattern is so strong, it gets put onto fairy tales that didn’t originally contain it. So for example, oral versions of “Little Red Riding Hood” did not include Little Red being eaten by the wolf. “Little Red Riding Hood” is not part of this family of tales about a woman’s development, from birth to marriage. But in the Grimm version, we have the disguise: Grandmother is really the wolf. And we have the death: Grandmother and Little Red in the wolf’s belly. The logical outcome would be for Little Red to marry the huntsman, and I bet someone has written or will write that version, because in fairy tales, patterns have a way of playing themselves out.

But anyway, back to our dying, disguised heroines. Why do they die? Why must they lose themselves?

My theory is that fairy tales reflect a mishmash of old stories, customs, rituals . . . and of course history. All sorts of things went into the making of fairy tales. Medieval famines went into them, and myths went into them, and the patterns of ritual went into them. I think that’s partly what we have here. What this death and disguise reminds me of, more than anything else, is a rite of passage. That pattern was described by Arnold Van Gennep in The Rites of Passage, which I read in graduate school. Van Gennep studied rites of passage from all over the world and concluded that they all share a three-part structure: they all have a pre-liminal stage, a liminal stage, and finally a post-liminal stage. So what is “liminal”?

A “limen” is a threshold: it’s the thing you cross over when you step through a door. At least, if you’re doing it in Latin! In a rite of passage, the pre-liminal state is stable: it’s the stage you were at before things changed. The post-liminal stage is also stable. So, for example, in a rite of passage you might change from a boy to a man, or an unmarried girl to a married woman. (I use those examples because they are two of the most common, and yes, rites of passage are usually gendered.) The liminal stage, between them, is unstable. It’s dangerous: to the person undergoing the rite of passage, and to anyone connected to that person. It must be closely supervised, protected by ritual. As traditional societies know, to change is to be in peril, at least for a while. The typical plot of the Victorian novel is this: “a rite of passage goes awry.” Usually the rite of passage is marriage, and poor Jane Eyre is left at the alter in her ritual wedding gown. What she must undergo next is a symbolic death on the moors, sleeping on the earth as though in a grave. I think it’s important that Charlotte Brontë made Jane’s rite of passage not marriage, but communion with the earth, which is described as a great mother.

Back to our fairytale heroine. It was once common for girls, as well as boys, to go through rites of passage. These tended to disappear over time . . . But the important thing, for understanding fairy tales, is that girls did once go through them, and the central stage of the rite of passage, the liminal stage, often involved a ritual death. Disguise was also a kind of death: young boys would be sent out into the wilderness, where they would ritually become animals. They were dead to the human community. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that just as society was losing so many of its traditional rites of passage, the color of a wedding dress changed. Yes, fashions were following Victoria, and white is the color of innocence, a virginal color . . . but it’s also the color of a shroud. I think that’s why in the West, white has stuck as wedding-dress color. A bride also looks like a corpse. So the girl undergoing a rite of passage is ritually dead, or ritually something other than what she is — she is in disguise.

That’s what we have in fairy tales: a memory, an echo, of the rite of passage.

It makes sense, doesn’t it? If these particular types of tales, the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey tales, were about the progress of a woman’s life, they would include a rite of passage in which she changes from a girl into a woman. That’s exactly what we have in “Snow White” and “Sleeping Beauty.” Some scholars have seen these instances of being dead as examples of extreme passivity, but because they occur so frequently in fairy tales, and are not always associated with being passive, I would call them times of transformation. It particularly interests me that they’re often associated with hearths. The Goose Girl must crawl into a hearth and whisper her secrets before she is recognized. Cinderella’s disguise comes from the hearth. Donkeyskin works in a kitchen, next to the hearth. Why a hearth? Well, for one thing, the hearth is a sacred space. It’s where food is cooked, where what is inedible is transformed into the edible. The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss identified the difference between raw and cooked as the central difference between primitive and civilized. The hearth is the symbol of civilization itself. It was once presided over by the goddess Hestia or Vesta, who is one of the most important goddesses of the classical pantheon. (We tend to forget her, because there aren’t a lot of stories associated with her. But in actual belief and ritual, Vesta was absolutely central. She’s the one to whom the Vestal Virgins owed allegiance, and they kept the sacred fire of Rome itself lit.) The hearth is where transformation happens, and it’s also a tomb. In ancient belief, life was most often seen as a cycle: before things were born, they had to die. The hearth is a symbol of that. And hearths were sometimes used for burials . . .

Is it all starting to make sense? What I haven’t yet touched on is what use we, as modern human beings, can make of this. But the important thing is that before she can reach her happy ending, the fairytale heroine has to die or lose herself in some way.

I was reminded recently of how this particular stage of the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey might be helpful in our modern lives, or at least to me. It was the end of the university semester. I was feeling tired and rather down, getting my work done but dragging myself through the days. I made it to Thanksgiving break, and all I wanted to do was watch British murder mysteries or baking competitions (which are surprisingly alike in their underlying narrative structure). I thought, what is wrong with me? I blamed myself — perhaps I had planned the semester wrong? (No, semesters are like this for every professor who teaches writing.) I tried to push myself, but every time I did, I just got more tired, more despondent.

And then I had a revelation: I’m not in the dark forest. I’m in the glass coffin.

If you’ve read the structure of the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey, you know that there is a stage where the heroine must go through the dark forest. It’s usually fairly early on in the tale. The important thing about the dark forest is that you don’t die there. You’re lost, you’re scared, you’re usually alone, after you get rid of the huntsman who was sent to kill you . . . but you’re not going to die. The dark forest is simply something you have to get through, and it usually represents your fears, your encounter with the darkness in yourself and the world.

The lesson of the dark forest is: keep going.

The stage where you die, where you end up in the glass coffin, is usually a separate stage. (Except in “Sleeping Beauty”: she’s dead and in the dark forest at once. In tale types, and in the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey, there’s always an exception.) The lesson of the glass coffin is that you will be revived. You will eventually wake up. In fairy tales, death is temporary. In this way, I think, fairy tales harken back to a pagan past and a time when life was seasonal, cyclical. The year died and was born again. The people who originally told these tales lived in continual cycles — of the seasons, of life and death, of the pagan or later Christian festivals that marked the stages of the year. Even their daily lives were governed by the rising and setting of the sun in a way ours aren’t. When they became Christian, death was still figured as a rebirth.

The lesson of the glass coffin is: rest now.

What does that mean? It means that sometimes you are tired, and sometimes you are in a state of transformation, and in those times you must accept that you need rest. Don’t keep going. Instead, crawl under the covers. Watch British murder mysteries and baking competitions. This isn’t the time to power through. The journey includes periods when you’re not traveling, and you need to accept that. Sometimes, you won’t be going anywhere for a while. And that’s all right.

So I did: I rested. And afterward I felt better.

It helped me to have a model of the journey, to understand where I was on that journey. Because the journey itself, and this is one of my hypotheses, is based on women’s actual lives. Oh, not the lives we live now: no, it’s based on what women’s lives were like hundreds of years ago. But the underlying structures of those lives, the leaving home, going through dark forests, finding friends and helpers . . . all those fundamental things are still parts of our lives, and learning the patterns can help us identify them in our own lives. They can help us live the lives we live now, consciously and well.

(The image is an illustration for “Snow White” by Marianne Stokes.)