Welcome to my essays website!

Although I am primarily a writer of novels, short stories, and poems, I have written a number of essays about fantasy and the fantastic, both for an academic and a general audience. This website collects many of those essays, so you can find and (I hope!) enjoy them here.

For a list of the essays included on this website, go to Contents, where you can click on any essay that interests you. If you just want to see a list of the essays I’ve written, you can find a bibliography on my author website: here. If you’re interested specifically in the Fairytale Heroine’s Journey project, look under Journey. If you would like to purchase a book of mine, look on the Purchase page.

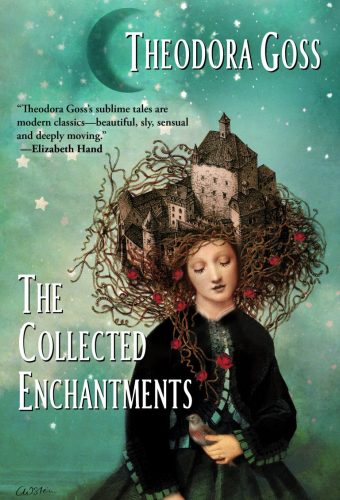

Below I have included my essay “Why I Write Fantasy,” originally published as the introduction to The Collected Enchantments.

Why I Write Fantasy

Imagine a girl, about twelve years old. She is sitting on a bench under a tree, reading a book. It is recess — this is in the days when schools had still had a proper recess after lunch — and the other children in her class are engaged in a game of kickball, except three girls who are sitting on the hillside overlooking the field, talking about their favorite celebrity crushes. But this girl is not interested in kickball — she is incapable of kicking the red rubber ball in the correct direction, or of catching it once it has been kicked. When she is required to play, during gym class, she always goes out into the field, between second and third base, to get as far away from the ball as possible. She does not understand why anyone would play kickball for fun. And her most recent crush was on Robin Hood, not exactly the sort of figure one can gossip about. (“Robin who? Is he in a band?” most of the girls in her class would say.) When she grows up, she wants to be either a writer or a sorceress, preferably with a tame dragon, a small one that can sit on her shoulder, sort of like a winged, scaly cat. She will live in a tower deep in the forest, far away from anyone, and either write or whatever sorceresses do. Either of those seem like good life goals.

That was me in elementary school. What was I reading? Probably one of the Narnia books, or The Hobbit, or something by E. Nesbit, Edward Eager, Astrid Lindgren — The Brothers Lionheart was my favorite. Later I would graduate to Anne McCaffrey’s Pern series, Tanith Lee’s Flat Earth novels, Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogy, Patricia McKillip’s The Forgotten Beasts of Eld, Madeleine L’Engel’s A Wrinkle in Time and its sequels. Some of the books I read were of higher quality than others, but I was not concerned with quality until much later. What I wanted was a magical secondary world — Pern, Earthsea, Narnia, Middle Earth. I did not realize until I was an adult why this particular aspect of fantasy was important for me: it spoke to my reality as an immigrant.

English was my third language. I was born in Budapest, Hungary, in the days of the Soviet Union, when there was still an Iron Curtain across Europe. The first books I read were collections of Hungarian and other European fairy tales. When I was five years old, my mother left Hungary, taking me with her, leaving behind the family and culture she had grown up in, for the hope of a better life in America. We moved first to Italy, then Belgium, and finally the United States, where I started school, speaking very little English — at that point I knew only Hungarian and French, and my Hungarian was fading fast. I remember the strangeness of encountering a new culture, with new food, new customs. Television taught me to ask for Wonder Bread and Campbell’s Soup from a can, to watch Saturday morning cartoons. Hungary became a country I vaguely remembered. Soon, I could no longer speak its language. Its food was served ceremoniously on special occasions: madártej and beigli at Christmas, húsos palacsinta at the parties my mother would occasionally throw for colleagues from work. We observed its special customs, celebrating our name days and Mikulás, the day Szent Miklós left chocolates and small presents in my shoes. We painted eggs at Easter. My mother still cursed in Hungarian, so I came to associate the language with powerful, forbidden words. To me, Hungary was a magical land — one to which we could not return because of the political situation. It might as well have been Narnia.

As an adult, I read two essays that define for me what fantasy is and can be. The first was Le Guin’s “A Citizen of Mondath” in her collection The Language of the Night. In it, she says that she first discovered the power of fantasy through reading Lord Dunsay’s A Dreamer’s Tales, in which he mentioned Mondath, one of the mysterious Inner Lands, “the lands whose sentinels upon their borders do not behold the sea.” Le Guin calls that reading experience “decisive. I had discovered my native country.” My native country is one of the Inner Lands. That is, Hungary is landlocked, bordered only by other countries, although it contains Lake Balaton, the largest freshwater lake in Europe, often called the Hungarian Sea. In Le Guin’s first serious attempt at a fantasy novel, she created the country of Orsinia, from her own name, Ursula (meaning “little she-bear”). The Latin ursinus, meaning bearlike, gives us the surname Orsini. Orsinia, located somewhat vaguely in Central Europe, was Ursula Country, although she had never been to Central Europe herself — that part of the world was essentially Narnia to her as well. I loved Le Guin’s Orsinian Tales, short stories set in her imaginary country. To me, they felt like home.

The second essay, actually the first chapter in an academic monograph, was by Katherine Hume. In Fantasy and Mimesis: Responses to Reality in Western Literature, Hume argues that “literature is the product of two impulses. These are mimesis, felt as the desire to imitate, to describe events, people, situations, and objects with such verisimilitude that others can share your experiences; and fantasy, the desire to change givens and alter reality.” In this formulation, fantasy is not a genre but a mode, a way of approaching literature and the primary world it inevitably describes — because as J.R.R. Tolkien points out in “On Fairy-Stories,” writing is always ultimately about our world, the one we inhabit. Fantasy approaches and examines that word in a different way, but there would be no Pegasus without the horse. Perhaps I should have added Tolkien’s essay to my list of influences, and it certainly is, but I read it later than I read Le Guin and Hume, so by the time he told me that fantasy can give us three fundamental things we all need in our lives, escape, recovery, and consolation, I already agreed with his argument. Those are certainly three things fantasy gave the twelve-year-old girl avoiding a kickball game by traveling in Nangiyala. What Hume taught me, around the time I started writing fantasy professionally myself, was that fantasy is neither separate from the larger world of fiction, nor fundamentally different from it. Both fantasy and realism are approaches to the world we inhabit. Indeed, once enough time has passed, all realism becomes fantastical. To us, living in the twenty-first century, the characters in Jane Austen’s novels are as unreal as Tolkien’s elves, as bound by strange customs, as obsessed with rings.

In “A Citizen of Mondath,” Le Guin writes that her Orsinian tales were not fantasy, exactly, but neither were they realistic. “Searching for a technique of distancing,” she had placed them in Central Europe, which was, at the time to most Americans, a mysterious, exotic location — Mittel Europa was like Middle Earth. After her Orsinia novel failed to sell, she started writing more clearly categorizable fantasy and science fiction; she had found her distancing technique. But to me, Central Europe was not distant. It was as close as letters to my grandparents, as beigli at Christmas, as my mother cursing in Elvish (well, it may as well have been). My stories about the Central European country of Sylvania were inspired in part by Le Guin’s Orsinian tales, but also in part by the fact that my grandmother’s family comes from what Hungarians call Erdély — that is, Transylvania, often translated as “Land Beyond the Forest.” Sylvania is not Transylvania; it inhabits the same vaguely Central European space as Orsinia. You can get to Vienna from there, but I can’t tell you the train station, or what landscapes the train will pass through. It’s a country of the imagination. Still, it’s more real to me than, for example, Los Angeles. I have been to Los Angeles, I have driven up and down its highways, and I’m still not entirely convinced that it exists.

There is a sense in which my childhood was fantastical. The reality I read about in the teen novels we were sometimes assigned in school, or that I read on my own out of curiosity, was not my reality. I think this is a common experience for immigrants. Like many immigrant children, my literary education had started with the fairy tales of my native culture. A certain way of looking at the world had been passed on to me, one in which supposedly dimwitted third sons always prevailed and white cats could turn out to be cursed princesses in disguise. Snakes and wolves and bears spoke, if not in English, then in Hungarian. It was better to be lucky than clever, and even better to be kind, because it was the kind girl who was showered with gold, and her lazy sister who had to go home covered in pitch. In that world, the most important rule of all, always and forever, was “Be polite to old women,” because they were inevitably fairies or witches, and both were equally dangerous.

It still seems to me that the world of fairy tales is more real than some of the supposedly realistic tales we tell ourselves. In “On Fairy-Stories,” Tolkien makes the same argument: automobiles, he says, are not necessarily more real than dragons. Both are creatures of the human imagination, and dragons have been around a lot longer than automobiles. Who knows what automobiles will turn into — perhaps some day we will get flying cars, and we will have mechanical dragons in the sky. Our perception of reality is so conditioned by imagination that at some level, we are all fantasists. We see trees and dream of dryads or Ents. We make up countries, pretending that there are lines on maps, and sometimes we build walls to make those lines real — but eventually the walls come down. What is real, finally, when the world we see is created by rays of light passing through the lenses of our eyes, focused and projected back to our retinas and then interpreted by our individual brains? I have great respect for consensual reality and the fact that, as Zen masters tell us, when I kick a rock, my foot will hurt. But we live in a world in which the stock market operates on the same principle as Tinkerbell — if we stop believing, it winks out of existence. It’s fairy gold.

In “Why are Americans Afraid of Dragons,” Le Guin writes that fantasy involves the free play of the imagination, and when Americans fear it, what they really fear is freedom. I suppose as a hyphenated American, I am only half afraid of dragons. Tolkien has taught me to be wary of them, McCaffrey to want one of my own. Like most writers, I’ll probably have to settle for a cat. Le Guin’s central point is that fantasy may not paint an accurate picture of our consensual reality, but it can reveal fundamental truths — such as the need to throw certain rings into volcanoes and stand up to dictators. In “The Critics, the Monsters, and the Fantasists,” she talks about another fundamental truth fantasy can reveal to us: it can move us beyond anthropocentrism. While literary realism is interested in the human — what we think, how we live — fantasy can show us the world from the perspective of a tree, or a laboratory rat, or an ant (all of which Le Guin has done). It seems to me that this is one of the most important functions of fantasy in our time. More than anything, in the twenty-first century, we humans need to get over ourselves, with our wars, our obsessive accumulation of money (itself an imaginary construct, as cryptocurrency has shown us), the fences we build to enforce those lines on the maps, to keep some of us in and some of us out. How different that territory would look from the point of view of a goose.

So why do I write fantasy? Perhaps because my experience of reality, as a Hungarian-American, was always fantastical, or perhaps because as an inhabitant of the twenty-first century, the world I see around me is more fantastical than most fiction. Tolkien wrote that literature comes from the great Cauldron of Story, into which have gone all the myths, legends, and fairy tales of human culture. What has gone into my particular cauldron of gulyás? The European tales I grew up on, certainly. My family history as well as the American suburbs I grew up in. Three language, the science fiction and fantasy I read growing up, the magical realism I studied in college, the English and American literary traditions I studied as a graduate student, from Chaucer to Toni Morrison. And my personal experiences growing up between two cultures, between Mikulás and kickball. Perhaps fantasy is simply my way of seeing and understanding the world, the shape those rays of light make on my retina. It took a long time for that twelve-year-old girl to become a writer. I’m still working on the sorceress part. I don’t yet have a tower in the depth of the forest, but I’m practicing my spells, and I’m sure at some point they’ll summon an appropriate dragon (or cat) to sit on my keyboard as I write. In the meantime, I will keep writing stories about third sons and cat princesses and the fundamental importance of being polite to old women, because you just never know.

This essay is reprinted here with the kind permission of Mythic Delirium Books. Many thanks to artist Catrin Welz-Stein for the gorgeous cover.