Fairies and Fairylands

by Theodora Goss

Fairies are the only fantasy creatures with their own magazine.

On a cold day in Colorado, after visiting the Botanical Gardens, I walked into the Tattered Cover bookstore. It was early spring, and the Botanical Gardens had been bare, just a few green shoots showing through the frost. In the bookstore, on the magazine racks, I saw a copy of Faerie Magazine. I flipped through it, and suddenly I was in Fairyland, where it is always summer and nothing ever dies, perhaps because it is already the land of the dead. What other fantasy creatures get their own magazines? There are no magazines for afficionados of trolls, selkies, or giants, although I imagine all of those creatures have their fans. But fairies have always had a particular hold on our imagination. If you flip open a copy of Faerie Magazine, you’ll see fairy lore, fairy recipes, entire fairy festivals, where ordinary people, accountants and teachers and owners of cupcake shops, all dress up as fairies, perhaps not realizing how dangerous it can be to imitate the Good People or People of Peace. Because fairies are dangerous, as we shall see. They are also, of course, alluring. Perhaps the secret of their allure is that they are the essence of fantasy, offering us the opportunity to visit Fairyland. (No other fantasy creatures get their own country either.) Like the best fantasy, they lure us away into another world, where magic is real and we can see marvels. White deer that flash through the forest. Apple trees that fruit and blossom at once. The Fairy Queen herself.

No wonder we dream of fairies, living in a mortal world where during parts of the year even the Botanical Gardens are covered with frost and all the magic of spring lies underground. We long for them as we long for magic, for the marvelous in our lives. But as I mentioned, they can also be dangerous. So what follows is a guide for those accountants and teachers and owners of cupcake shops, who represent us all. In case they encounter fairies, which is entirely likely.

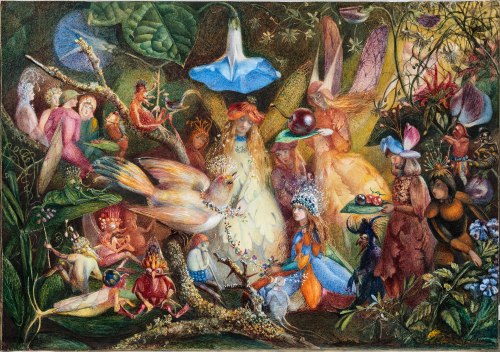

(The Fairies’ Favourite by John Anster Fitzgerald)

I. What Are Fairies, Anyway?

That’s a good question. And there’s no one answer to it.

According to Katherine Briggs, who wrote both The Encyclopedia of Fairies and The Fairies in Tradition and Literature, two essential guides to the subject, the word fairy can be used in two ways: “The first is the narrow, exact use of the word to express one species of those supernatural creatures ‘of a middle nature between man and angels’ — as they were described in the seventeenth century — varying in size, in powers, in span of life and in moral attributes, but sharply differing from other species such as hob-goblins, monsters, hags, merpeople and so on.” The second is a more general sense of the world to mean any magical creature that is not an angel, devil, or ghost (Briggs, Encyclopaedia xi). The first sense of the word is the one we want here, because hob-goblins and hags, no matter how fascinating, are not our subject. We want to know about fairies specifically. And I will confine this particular article to the fairies of the British Isles. Fairies and fairy lore are found all over the world, but there is simply too much material to discuss it all here. So those of you traveling to France or Greece will need to do some additional research to make certain that your fairy encounters are as safe and productive as possible. However, there are certain common elements among fairies from different countries, so what follows will provide you with at least a basic guide.

Briggs tells us that the word fairy itself was not used in Britain before the medieval era. It comes from the French fai, which can be traced back to the Italian fatae, magical women who visit after the birth of a child to pronounce its future. Those magical women were originally the Roman Fata or fates, whom even the gods feared. The native British term was elf, from the Old English aelf and the Old German alp, a word that in modern German means “nightmare.” This was the term J.R.R Tolkien preferred, and which he used in The Hobbit. Tolkien was reacting in part to the popular notion of fairies, going back to at least the Renaissance, as diminutive nature spirits. Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language, first published in 1755, defines a fairy as a “Fabled being supposed to appear in a diminutive human form, and to dance in the meadows” (qtd. in Latham 1). This definition does not describe the Fairy Queen who met True Thomas under the Eildon Tree, but it does represent a view of fairies that has persisted through Victorian fairy paintings and Disney movies. The idea that fairies are necessarily diminutive is reinforced by the popular Cicely Mary Barker series of Flower Fairies books. Tolkien, who mentions his own childhood disdain for “flower-fairies and fluttering sprites with antennae,” believed that William Shakespeare and his contemporaries were responsible for the diminutive stature of fairies (Tolkien 36), but Briggs points out that in British folklore, fairies have always been various sizes, large and small.

We find this variety in two descriptions of fairies, one by William Blake and one by Rudyard Kipling’s Puck in Puck of Pook’s Hill. Blake, who believed in fairies, is reported to have had the following conversation:

“Did you ever see a fairy’s funeral, madam?” said Blake to a lady who happened to be sitting next to him. “Never, Sir!” said the lady. “I have,” said Blake, “but not before last night.” And he went on to tell how, in his garden, he had seen “a procession of creatures of the size and colour of green and grey grasshoppers, bearing a body laid on a rose-leaf, which they buried with songs, and then disappeared.” (qtd. in Briggs, Fairies 162)

Blake’s fairies are diminutive and insect-like, the sorts of fairies that Tolkien despised as a child. Puck describes the fairies he knows quite differently:

Can you wonder that the People of the Hills don’t care to be confused with that painty-winged, wand-waving, sugar-and-shake-your-head set of imposters? Butterfly wings indeed! I’ve seen Sir Huon and a troop of his people setting off from Tintagel Castle for Hy-Brasil in the teeth of a sou’westerly gale, with the spray flying all over the castle, and the Horses of the Hill wild with fright. Out they’d go in a lull, screaming like gulls, and back they’d be driven five good miles inland before they could come head to wind again. Butterfly-wings! (qtd. in Briggs, Fairies 203)

Puck’s fairies are closer to the fairies of the medieval ballads, the sorts of fairies you’d expect to see on the Wild Hunt. But both sorts of fairies are part of the tradition.

There are two popular explanations for the origin of the fairies. According to the first of these, fairies had once been angels. When Lucifer was banished, the angels who had rebelled were banished with him. There were also angels who had not rebelled, but had not fought on God’s side either. God said to them,

There is something I must be telling you. I cannot keep you any longer in Heaven, because you are not with Me — and those that are not with Me are against Me. That is why I am not keeping you among my good angels any longer. But I am sending you down beyond the curtains of mist, to the world that is called the Earth, and there you are to live under the ground and in the hills as a Little People; and the people of the Earth will call you the fairies. I will not take away the wings from you, and when the moon is full you can come out from your fairy hills and exercise them, in case a time should come when I think you are fit to be recalled to Heaven and you would be needing your wings again. (qtd. in Drever 21)

This story places the fairies within a Christian religious context, although it seems clear that the fairies predated Christianity in Britain. In “Thomas the Rhymer,” the Fairy Queen shows True Thomas three roads. The first is a “narrow road, / So thick beset wi’ thorns and briers,” which goes to Heaven; the second is a “braid, braid road / That lies across that lily leven,” which goes to Hell; and the third is a “bonny road / That winds about the fernie brae.” The third road goes to Fairyland. It is clear that Fairyland represents a third way, neither Heaven nor Hell, that lies outside orthodox Christianity. Perhaps that is why fairy morality is so different from our own. According to Briggs, although there are good and bad fairies in literature, particularly in the French fairy tales that have given us so many of our Disney movies, “in folklore a good fairy is a fairy in a good temper, and a bad fairy is one that has been offended” (Fairies 108).

The other popular explanation is probably also the older one, predating Christianity: that fairies are the dead. Briggs tells the story of a young man who found himself among fairies because he had stayed out too late on Halloween night: “He met Finavarra the Fairy King and Oonagh his Queen; they gave him fairy gold and wine and were full of merriment, but for all that they were a company of the dead. When he looked steadily at any one of them he found him to be a neighbor who had died — perhaps many years before” (Fairies 15). Perhaps that is why it is dangerous to eat fairy food. In the Cornish tale “The Fairy Dwelling on Selena Mor, “a farmer found himself at a fairy feast and met his former sweetheart, who was thought to have died several years before. She tells him that she was required to stay in fairyland after eating a plum from the orchard, and warns him not to eat anything lest he have to stay there as well. But her caution does little good: “Like many other visitors of Fairyland,” he “pined and lost all interest in life after this adventure” (Fairies 19). This story is reminiscent of the myth of Persephone, who was forced to stay in Hades because she had eaten pomegranate seeds. The similarities suggest that Fairyland is also the land of the dead. As Briggs points out, “the distinction between the fairies and the dead is vague and shifting” (Fairies 51).

Perhaps the connection between fairies and the dead explains why fairies are usually found underground, under mountains, hills, or lakes. Throughout the British Isles, there are specific underground places associated with fairies. Lady Wilde gives a particularly evocative description of a lake dwelling:

Down deep, under the waters of Lough Neagh, can still be seen, by those who have the gift of fairy vision, the columns and walls of the beautiful palaces once inhabited by the fairy race when they were the gods of the earth; and this tradition of a buried town beneath the waves has been prevalent for centuries amongst the people. (qtd. in Briggs, Fairies 24)

There are also magical islands off the coast of Ireland and Wales that belong to the fairies. The island of Hy Brasil, a fairy island in Irish folklore, may have given its name to Brazil (Tolkien 35). In those places, fairies keep their revels, to which humans are sometimes invited. But those who accept the invitation are often sorry they did so. Time passes differently in Fairyland, so a farmer who wanders into the hillside and dances with a fairy woman will sometimes wander out again, a hundred years after he had gone in, to find his friends long dead and himself forgotten. This was the fate of the Irish hero Ossian, who went to Fairyland to be with his fairy mistress. In The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries, W.Y. Evans-Wentz records that Ossian rode away with her on a white horse, across the ocean, presumably to one of those magical islands. When he had been with her for some time, he wished to return and see how his Fenian Brotherhood had fared. She warned him that Ireland had changed, and that he should not touch his foot to the ground. He rode the white horse back over the waves, only to find that hundreds of years had passed and the Fenians were dead. While riding through a countryside so altered that he barely recognized it, he noticed men trying to move a stone under which some of their fellows had become trapped. He leaned down to help them, but the girth of the saddle broke and he fell upon the ground. In a moment, the white horse had fled, and Ossian had grown old (Evans Wentz 346-7).

The connection between fairies and particular places reveals what probably went into the making of fairies and the stories about them. They are most likely a combination of the pagan gods worshiped before the advent of Christianity; aboriginal peoples who were pushed to the margins, the mountains or hillsides, with each new conquest; and personifications of natural places and phenomena, which have been a part of human beliefs as far back as those beliefs have been recorded.

(The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke by Richard Dadd)

II. I Met a Fairy. Now What?

Well, you’re in trouble, that’s what.

Or you could be, if you’re not careful. Most encounters with fairies are brief, and pass without incident as long as human observers do not interfere with the fairy folk. Folklorists have recorded a number of such encounters. R.L. Tongue, who traveled to Women ‘s Institutes throughout Somerset to collect fairy and folk tales, collected the following tale from the President of the Women’s Institute in the town of Wellington:

When we were on holiday in Cornwall my daughter and I came down by a winding lane, and all of a sudden there was a small green man by a gate watching us. All in green, with a pointed hood and ears. We both saw him, and my little girl screamed — she’s psychic — and we were cold with terror. We ran for the ferry below. It was going across, but it came all the way back to pick us up. No one said a word, but they didn’t think we were silly. I don’t think I’ve ever been so frightened. (qtd. in Briggs, Fairies 132)

This is a fairly typical account, involving just a glimpse of the fairy, and the President and her daughter were wise to run. As Briggs points out, “the fairy had seen them before they had seen it, and it was therefore dangerous” (Fairies 132).

Not all encounters are so innocuous. Fairies are notorious for interfering with the human world, and particularly for abducting human beings. Human women are routinely abducted to care for fairy children, as midwives at their birthing or as nursemaids. However, the greatest danger is to human children, who may be stolen away and replaced by fairy children, called changelings. A human mother may wake up one morning to find that her child, once plump and smiling, is now old, wrinkled, and ugly. If she suspects that the child may be a changeling, she should do something so unusual that the changeling will have to remark on it. In Irish Fairy and Folk Tales, W.B. Yeats records a changeling story in which the mother was advised to boil eggshells in a pot of water. When the changeling asked what she was doing, she replied that she was brewing eggshells. “‘Oh!’ shrieked the imp, starting up in the cradle and clapping his hands together. ‘I’m fifteen hundred years in the world, and I never saw a brewery of eggshells!’” She ran toward the changeling, intending to throw it into the pot of boiling water, but when she got there, it was gone and her own baby lay in the cradle (Yeats 68). The brewery of eggshells is a traditional and relatively gentle means of testing a potential changeling. Other more violent means include throwing it on a fire or leaving it out in the snow. Stories of changelings sometimes had unfortunate and very real consequences. Children with congenital deformities, infantile paralysis, or mental illness were sometimes though to be changelings, and were treated as such. According to Briggs, even at the beginning of the twentieth century “a child was burned to death in Ireland when the neighbors put him on a hot shovel” (Fairies 117).

Adults are abducted by fairies as well, but as we have seen, not all visits to Fairyland are involuntary. Lady Wilde records the case of a young man who “died suddenly on May-Eve while he was lying asleep under a hay-rick.” His parents immediately knew that he had been carried off by the fairies, and they called a fairy doctor, who promised to bring him back in nine days.

Now on the ninth day a great crowd assembled to see the young man brought back from Fairyland. And in the midst stood the fairy doctor, performing his incantations by means of fire and a powder which he threw into the flames that caused a dense grey smoke to arise. Then taking off his hat, and holding a key in his hand, he called out three times in a loud voice, “Come forth, come forth, come forth!” On which a shrouded figure slowly rose up in the midst of the smoke, and a voice was heard answering, “Leave me in peace; I am happy with my fairy bride, and my parents need not weep for me, for I shall bring them good luck, and guard them from evil evermore.” (qtd. in Briggs, Fairies 126)

The parents were pleased that their son was content in Fairyland, so they gave the fairy doctor presents and sent him home. Of course, a fairy could also leave Fairyland for a beloved mortal. Evans-Wentz even records a fairy woman who followed the man she loved to America (Briggs, Fairies 127).

As you might suspect from Lady Wilde’s tale, the fairy doctor was an important figure, and the power he wielded, or claimed to wield, was subject to abuse. According to Terri Windling, “The most famous case of ‘fairy doctoring’ involved a grown woman in 1895, and riveted newspaper readers all across the British Isles. This was the murder of Bridget Cleary, a handsome young Irish woman who was killed by her husband, family, and neighbors because they thought she was a fairy changeling.” When Bridget fell sick with what may have been pneumonia, her husband consulted a fairy doctor. The fairy doctor told him that the sick woman was a changeling, and that the real Bridget had been abducted by the fairies who lived in a nearby hill. Bridget was subjected to a variety of tests: tied to her bed, sprinkled with holy water, and eventually burned to death. Her husband, convinced that he had killed the changeling rather than Bridget, waited for her by the fairy hill, but the real Bridget never came out. He was eventually prosecuted for murder.

Fraud involving the fairies has been a problem throughout their history. In 1613, John West and his accomplice Alice West were convicted at the Old Bailey for pretending to represent the king and queen of the fairies, asking for money in exchange for preferential access to their fairy majesties. They managed to defraud wealthy men and women of substantial sums, and even convinced a servant girl to sit naked in the garden on a cold winter ‘s night with a pot of earth in her lap, believing the fairy queen would turn it into gold by morning, while they ran away with her savings and clothes. They were eventually whipped through London, made to stand in a pillory, and imprisoned in Newgate (Halliwell 181-6). The Cottingley Fairies affair was quite a different matter. In 1917, two cousins, Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright, claimed to have photographed fairies in the forest near Elsie’s house. Elsie’s mother took the photographs to the theosophist Edward Gardner, who passed them on to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, inventor of Sherlock Holmes. Conan Doyle was considerably less skeptical than his detective would have been: he believed the photographs were genuine and wrote an article about them for The Strand Magazine. He also provided the girls with a camera and asked them to take more photographs if they could. They produced another three, for a total of five. The girls maintained that the photographs were genuine for many years, but toward the end of their lives they admitted that they had simply photographed paper cutouts (Briggs, Fairies 238-9). These fairy frauds suggest that ordinary human beings are as tricky as, if not trickier than, the fairies themselves.

How can you keep your encounters with fairies, real fairies, safe and productive? First, don’t call them fairies: Good People or People of Peace are safer names to use. Second, don’t destroy their dancing places or sacred trees. Respect their animals, which are usually white and red. When you speak to them, don’t ask for their names or give them your own. Tell the truth, and don’t try to bargain. Avoid dancing with them or participating in their revels, and never eat fairy food. If possible, carry iron, which can help you escape from a fairy hill. Watch out for the Wild Hunt, when fairy huntsmen race their horses across the sky, in full chase, their hounds baying. And if you meet the Fairy Queen, well. Just do as you ‘re told, even if it means you have to serve her for seven years and tell the truth for the rest of your life.

(Titania and Bottom by Henry Fuseli)

III. I Want to Write about Fairies

Good for you. You’re going to be part of a long and varied literary tradition.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first mention of fairies in English literature occurs in Beowulf, where “eotenas ond ylfe ond orcneas,” “etins and elves and evil spirits,” are described as the descendants of Cain. However, the fairies we know, living in Fairyland and ruled by their beautiful, dangerous queen, first appear in medieval ballads such as “Thomas the Rhymer.” There is no better description, anywhere in English literature, of the Fairy Queen than in that ballad:

True Thomas lay on Huntlie bank;

A ferlie he spied wi’ his e’e;

And there he saw a ladye bright

Come riding down by the Eildon Tree.Her skirt was o’ the grass green silk,

Her mantle o’ the velvet fyne;

At ilka tett o’ her horse’s mane

Hung fifty siller bells and nine.

Fairies were important to Shakespeare and his contemporaries in the Renaissance. According to Minor White Latham, “Literary England, as well as ordinary England, court and citizen, witnessed them in pageants and royal processes, saw them represented on the stage, played the role of the fairies in masques and in practical jokes, read of them in poems and pamphlets, and sang of their beauty and power, not forgetting to make use of a charm against their wickedness on going to bed” (17). In addition to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which introduced us to Titania and Oberon feuding over a changeling child, the Renaissance gave us Spenser’s Faerie Queene, in which Queen Elizabeth I was represented as Gloriana, the Faerie Queene of the title, as well as Michael Drayton’s Nymphidia, which Tolkien called “as a fairy story (a story about fairies), one of the worst ever written” because of the way in which it diminished his beloved elves (36).

Fairies became important again in Romantic and Victorian poetry and prose. The knight of John Keats’s “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” tells us, “I met a lady in the Meads, / Full beautiful, a faery’s child,” with long hair, light foot, and wild eyes. She takes the Knight to her “elfin grot” where, lulled to sleep, he dreams of all the knights in her thrall and realizes that he too has become her captive. All of these literary works were adult fare. It was not until the Victorian era that fairies were considered appropriate for children. That era gives us some of the most important children ‘s books about fairies, such as Jean Ingelow’s Mopsa the Fairy and Andrew Lang’s series of colored fairy books. George McDonald’s novel Phantastes also belongs to the Victorian era. It is an unusual novel, a fairy tale for adults in an era when fairies were being relegated to the nursery, about a protagonist named Anodos (or “on no road”) who goes on an allegorical journey through Fairyland. Fairies were reappropriated for adults in the modern era, when Yeats wrote about them as the gods of Ireland and Tolkien attempted to return the elves to their ancient glory. Drayton’s Pigwiggen, who rides on an earwig, can scarcely be placed in the same category as Elrond, Lord of Rivendell, yet they both come from the same fairy tradition.

That tradition is broad and deep. It includes beautiful Fairy Queens, castles beneath Lough Neagh, the sorrows of Ossian, and the Cottingley Fairies cutouts. What form will it take next? That will be up to us. We are, after all, the fairies’ chroniclers. Indeed, they may believe that we exist to visit their haunts, bake their recipes, and dress as we think they do, although they may laugh at our wings. And while we long for the magical and marvelous in our lives, the flash of the white deer in the forest, crocuses pushing through frost, we will read about them and continue telling their stories.

(Midsummer Eve by Edward Robert Hughes)

(This essay was originally published in the Folkroots column of Realms of Fantasy, June 2011.)

Research Sources:

Briggs, Katherine. An Encyclopaedia of Fairies. Pantheon Books, 1976.

—. The Fairies in Tradition and Literature. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1967.

Latham, Minor White. The Elizabethan Fairies. Octagon Books, 1972.

Matthews, John and Caitlin, eds. A Fairy Tale Reader. Aquarian/Thorsons 1993.

Tolkien, J.R.R. “On Fairy Stories.” The Tolkien Reader. Ballantine Books, 1966.

Windling, Terri. “Changelings.” Journal of Mythic Arts. Spring 2003.

—. “Fairies in Legends, Lore, and Literature.” Journal of Mythic Arts. Spring 2006.

Yeats, W.B. Irish Fairy and Folk Tales. Barnes & Noble, 1993.